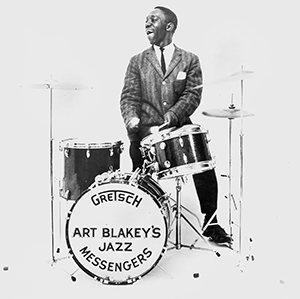

Art Blakey

by Rick Mattingly

Art Blakey’s stated goal was to be a great drummer. “But,” he told writer Chip Stern in a 1984 Modern Drummer cover story, “just in the sense of having musicians want to play with me—not to be better than Buddy Rich or to compete with someone. I will not compete that way; I’ll compete through my band. If musicians have a preference and they say ‘I want to play with Bu,’ that just knocks me out. And I’ll ask, ‘Is there anything I can do to make you sound better? What do you want me to do when you play?’ My head never got so big that that wasn’t my goal—to play with people.”

Art Blakey’s stated goal was to be a great drummer. “But,” he told writer Chip Stern in a 1984 Modern Drummer cover story, “just in the sense of having musicians want to play with me—not to be better than Buddy Rich or to compete with someone. I will not compete that way; I’ll compete through my band. If musicians have a preference and they say ‘I want to play with Bu,’ that just knocks me out. And I’ll ask, ‘Is there anything I can do to make you sound better? What do you want me to do when you play?’ My head never got so big that that wasn’t my goal—to play with people.”

For many jazz musicians in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, the goal was to play with Art Blakey. Among the notable players who were members of Blakey’s group, the Jazz Messengers, are pianists Joanne Brackeen, Keith Jarrett, Mulgrew Miller, Jaki Byard, Horace Silver, Bobby Timmons, Cedar Walton, and James Williams; saxophonists Gary Bartz, Kenny Garrett, Lou Donaldson, Benny Golson, Branford Marsalis, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Wayne Shorter, Ira Sullivan, and Bobby Watson; trumpet players Terence Blanchard, Clifford Brown, Donald Byrd, Kenny Dorham, Freddie Hubbard, Chuck Mangione, Wynton Marsalis, Lee Morgan, Wallace Roney, and Woody Shaw; trombonists Robin Eubanks, Curtis Fuller, and Slide Hampton; and bassists Wilbur Ware, Reggie Workman, Stanley Clarke, and Lonnie Plaxico. “All the cats who played with me are like my family,” Blakey said.

When Blakey died in 1990, his obituary in The New York Times included this comment from Max Roach: “Art was an original. He’s the only drummer whose time I recognize immediately. And his signature style was amazing; we used to call him ‘Thunder.’ When I first met him on 52d Street in 1944, he already had the polyrhythmic thing down. Art was perhaps the best at maintaining independence with all four limbs. He was doing it before anybody was.”

But despite his technical abilities, Blakey was known for a more straight-ahead style of timekeeping than most of his bebop contemporaries. He typically maintained a strong hi-hat on beats 2 and 4, made sure there was no doubt as to where “1” was, and instead of setting up sections and phrases with elaborate fills, he would lead into them with powerful press rolls. Blakey is also credited with originating the oft-used cross-stick on beat 4 and of inspiring the development of riveted cymbals by hanging his key ring over the wingnut of his ride cymbal to produce a sizzle effect.

“I just wanted to hear something different—to experiment,” Blakey told Modern Drummer. “I always liked to innovate with different sounds on the drums when I started to play, because I came out of that era when the drummer played for effects. I had to learn to play a show in almost a standing position. I had to keep the bass drum going, grab this and blow that, and do a roll. But that was fantastic because it helped me get where I wanted to go and helped me find out what it was I wanted to do.”

His induction into the PAS Hall of Fame is but the latest in a long list of awards, including the 1976 Newport Jazz Festival Hall of Fame, the 1981 Downbeat Jazz Hall of Fame Readers’ Choice Award, the Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies Hall of Fame, the 1984 “Best Instrumental Jazz Performance” Grammy for the New York Scene album, the 1985 Gold Disc award from Japan’s Swing Journal for the album Live at Sweet Basil, an honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music, and the 2001 Grammy Hall of Fame Award for the album Moanin’.

Art Blakey was born on October 11, 1919 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to a single mother. She died soon after he was born and he was raised by a family friend, not knowing until years later that his foster mother was not his real mother. He received some piano lessons in school, and by the time he was in seventh grade he was working professionally. He landed a steady gig at a club owned by a gangster, and one night, after having worked at the club for two years, a young Erroll Garner sat in on piano. When the club owner heard Garner, he ordered Blakey to switch to drums. “So I just went up there and played the show [on drums],” Blakey recalled. “How, I’ll never know, but I made it.”

Blakey learned to play drums on the job. “I used to play every night,” he said. “It didn’t matter how much money I was making, I just had to play every night. When we’d get through playing at night, it was daybreak. Then we’d play the breakfast show. After that we’d have a jam session, which would go on until like 2:00 in the afternoon. So maybe by 3:00 I’d get to bed, and I’d be back in the club again at 8:30. So I never stopped. I was playing all the time, so I didn’t have to worry about practicing. But when I did, I’d usually just practice on a pillow. I’d never practice on a pad because a pillow would make me pick up my sticks instead of depending on the rebound of the pad.”

Blakey also learned from watching and getting advice from other drummers in Pittsburgh. “There was Klook [Kenny Clarke], there was a drummer named Jimmy Peck, and then there was a guy named Sammy Carter,” Blakey said. “But the guy I learned the most from in Pittsburgh was a guy named Honeyboy. That’s the cat who taught me how to play shows.” Blakey also received some instruction from Chick Webb, who once sat Blakey down with a snare drum and a metronome, set the metronome to a very slow tempo, and told Art to roll for a hundred beats. “And if you stop, I’ll break your skull,” Webb said. “He was a disciplinarian,” Blakey said.

In 1942 Blakey went to New York to play with Mary Lou Williams, and then he toured with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra for about a year. Blakey then led a big band in Boston for a short time before going to St. Louis to join Billy Eckstine’s band, with whom he played from 1944–47 alongside such musicians as Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, and Fats Navarro.

In 1948, Blakey traveled to Africa where he learned about polyrhythmic drumming and Islamic culture, taking the name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina, which led to his nickname, “Bu.” But Blakey never cited Africa as the roots of his music. “Since so many of the great jazz musicians are black, they try to connect us to Africa,” he said in the ’84 interview. “But I’m an American black man. We ain’t got no connection to Africa. I imagine some of my people come from Africa, but there are some Irish people in there, too. I’m a human being and it don’t make no difference where I come from.

“And they’re trying to put [jazz] off in the corner as being black,” he added. “Jazz is American; it ain’t got a damn thing to do with color. I’ll take kids from any part of the world; if they want to play jazz, I’ll put them in my band and they’ll play jazz—and really play it, too.”

Over the next few years, Blakey worked with Lucky Millinder, Earl Hines, and Buddy DeFranco, and he recorded with Thelonious Monk. He began co-leading quintets with Horace Silver in 1953. They recorded several albums with different personnel, including Kenny Dorham, Lou Donaldson, Clifford Brown, and Hank Mobley. One album was released under Silver’s name, but another was released under the name Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, and when Sliver left to start his own band, Blakey kept the Jazz Messengers name for the rest of his career.

In 1959, tenor saxophonist Benny Golson joined the quintet and soon after was joined by what became the best-known lineup of the Jazz Messengers: tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, trumpeter Lee Morgan, pianist Bobby Timmons, and bassist Jymie Merritt. The songs written during that period became trademarks for the band, including Timmon’s “Moanin’,” Golson’s “Along Came Betty” and “Blues March,” and Shorter’s “Ping Pong.” In 1961, the group became a sextet with the addition of trombonist Curtis Fuller, giving the hard-bop band more of a big band sound.

The Jazz Messengers began recording for Blue Note records and became a mainstay on the jazz club circuit through the 1960s. They also toured Europe and North Africa, and in 1960, they became the first American jazz band to play in Japan.

In the early 1970s, along with his work with the Jazz Messengers, Blakey made a world tour with the Giants of Jazz, which included Dizzy Gillespie, Kai Winding, Sonny Stitt, Thelonious Monk, and Al McKibbon. He also participated in a legendary drum battle with Max Roach, Buddy Rich, and Elvin Jones at the 1974 Newport Jazz Festival.

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, the Jazz Messengers remained a vital force in jazz, introducing numerous musicians who would go on to have major careers of their own. “My current band is pretty good,” he told Modern Drummer in 1984, “but I’m going to switch up the guys pretty soon. There are so many young kids out there who need the opportunity. I don’t want nobody in my band too long, because when cats stay too long, they get complacent, get big heads, and then it’s time to get out, buddy, because there are no stars in this band: The band is the star. Besides, I like to hear different interpretations. About my favorite Jazz Messenger group was the one with Wayne [Shorter], Freddie [Hubbard], Curtis [Fuller], Jymie [Merritt], and Cedar [Walton]. Musicians like that don’t come along all the time, but if you keep combing the woods, one will turn up sooner or later. And when they get strong enough to be on their own, I let them know it—time to do your own thing. See, a lot of things that happen in my band I don’t agree with, but I want to give it a chance to develop because there are some heavy young people out there.

“The idea of playing jazz is to be professional enough to make a mistake, make the same mistake again, and then make something out of that,” Blakey said. “That’s jazz! And if you ain’t professional enough to do that, then you ain’t a professional jazz musician. I’m not saying you’re not a good musician, but if you don’t know your instrument enough to go back and make that mistake twice, and do something creative with it, forget it, because that’s how jazz was born: Somebody goofed.”

During the later years of his career, Blakey had lost much of his hearing. “The only thing I can hear is music,” he said. “I can hear vibrations. I take my hearing aid off when I’m on the bandstand, and I can hear better than the other musicians; I know when they’re out of tune.”

The first thing many people think of when Art Blakey’s name is mentioned is all of the great musicians who apprenticed in the Jazz Messengers. His drumming didn’t have the flash, complexity, or speed of drummers like Buddy Rich, Elvin Jones, Max Roach, or Joe Morello, but it had personality—something Blakey found lacking in many younger drummers. “They all sound like they came off a conveyor belt because they don’t identify themselves,” he said. “There’s no originality, and this is blocking the advancement of the instrument. People don’t care how many paradiddles you can play; people only know what they feel. You can take a drum and transport people. I was taught by Chick Webb that, if you’re playing before an audience, you’re supposed to take them away from everyday life—wash away the dust of everyday life. And that’s all music is supposed to do.”

Above all, Blakey’s goal was to serve the musicians he was playing with. “The drummer is supposed to play in the rhythm section. So if drummers come out of there and start playing for themselves, then it’s all lost,” he said.

“Art Blakey was the first drummer my drum teacher had me listen to, way back in 1959,” Peter Erskine recalls. “His drumming was swinging, hard-driving, raw, unabashed, and unapologetic. Visceral—but what five-year-old kid knows the word ‘visceral’? Five-year-old-kids recognize honesty, however, and Blakey was as honest a drummer as the day was long. Art just played. As high-fidelity recording techniques got better and better, drums seemed to become more and more popular on LP albums, and Blakey’s name and sound were part of many multiple-drummer recordings including Gretsch Night at Birdland, Drum Suite, and The African Beat, all listening staples in our home. There was so much power coming out of Blakey’s drums that I imagined him to be a giant of a man. When my father took me to see Blakey at the Show Boat jazz club in Philadelphia at a Sunday matinee, I was amazed to see Art Blakey in person, standing on the sidewalk outside of the club. He was not eight-feet tall, as I had imagined! He was, instead, a very kind man, small in physical stature but huge in heart and power.

“Blakey proved to be the most important mentor in jazz, introducing one great jazz talent after another by way of his Jazz Messengers—players who would go on to enjoy giant careers themselves,” Erskine says. “Perhaps the most telling aspect of Blakey’s power as a bandleader and mentor was reflected in the relationship I had with Jazz Messenger alum Wayne Shorter during our four-year collaboration in the group Weather Report. Hardly a day would go by without Wayne telling some story or recounting an anecdote or life-story lesson that was about Art Blakey. In contrast, Wayne almost never brought up the name of his other boss, Miles Davis. It was always ‘Art this’ and ‘Art that’ with Wayne.

“I submit that is has always been ‘Art this’ and ‘Art that’ for all of us drummers, too. I am delighted that the Percussive Arts Society is honoring Art Blakey by way of the Hall of Fame. Blakey’s quote, ‘Music washes away the dust of everyday life,’ is reason enough to honor and admire this man for the ages.”